What it’s about

I’ve been collecting snapshots for almost my entire adult life. I’ve tried to quit a few times, but snapshots have always stood by me. Somehow they won’t give up, even as other pursuits have come and gone. That doesn’t mean I’ve always looked at them the same way.

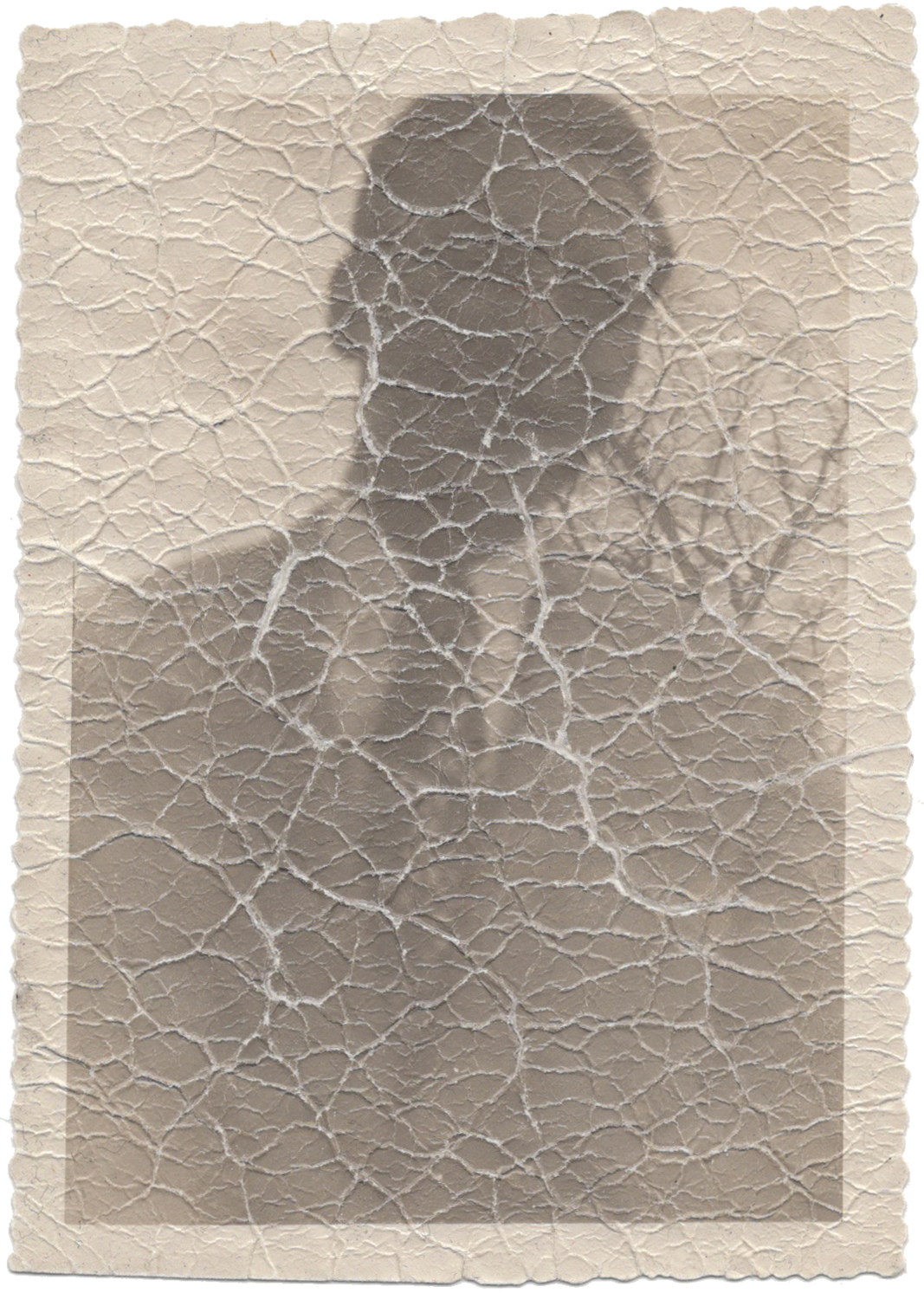

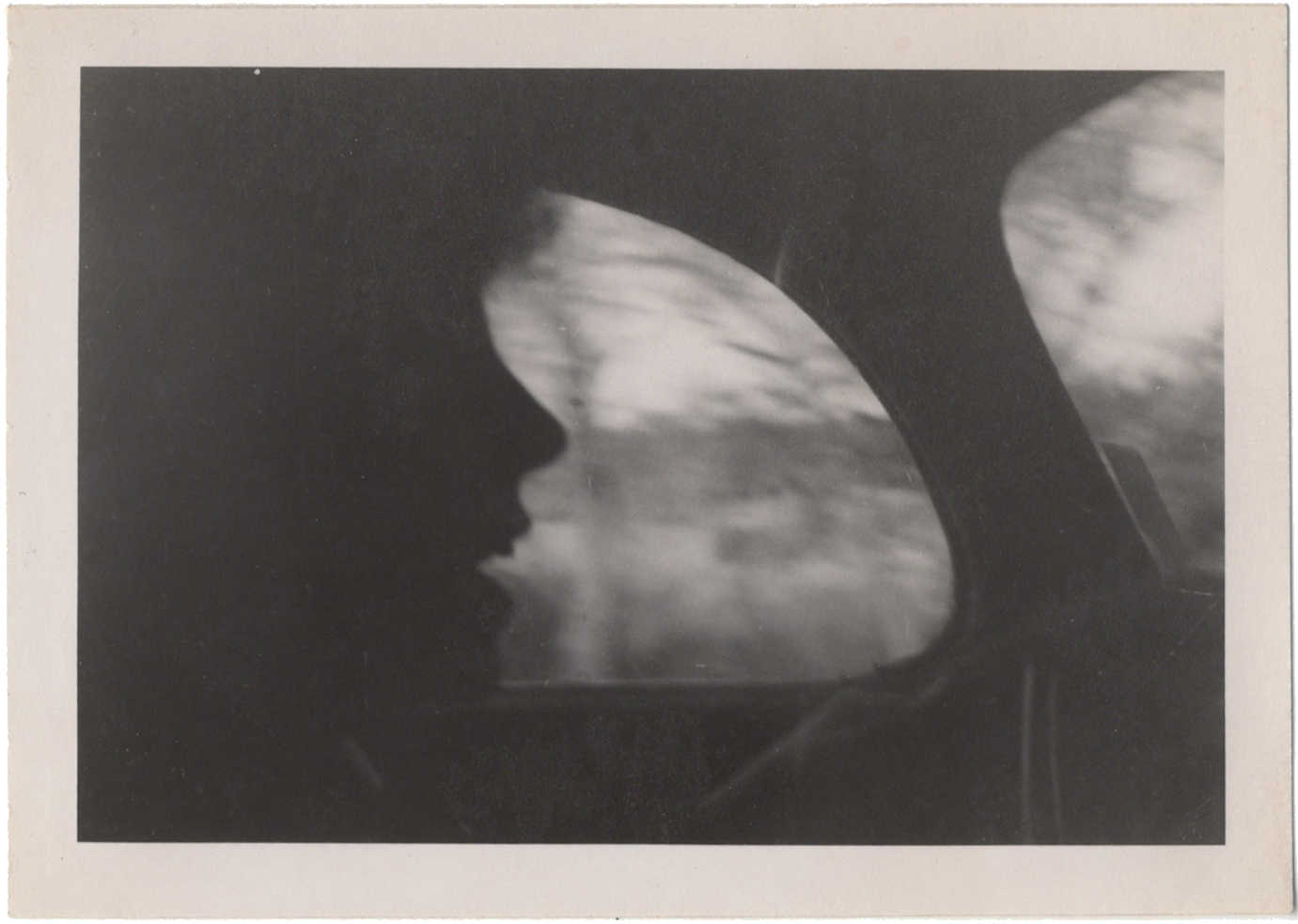

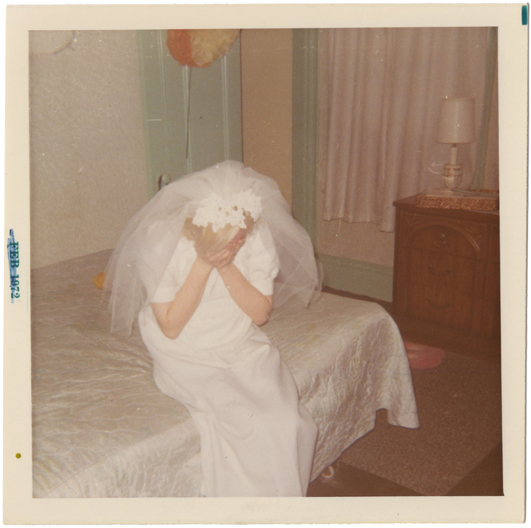

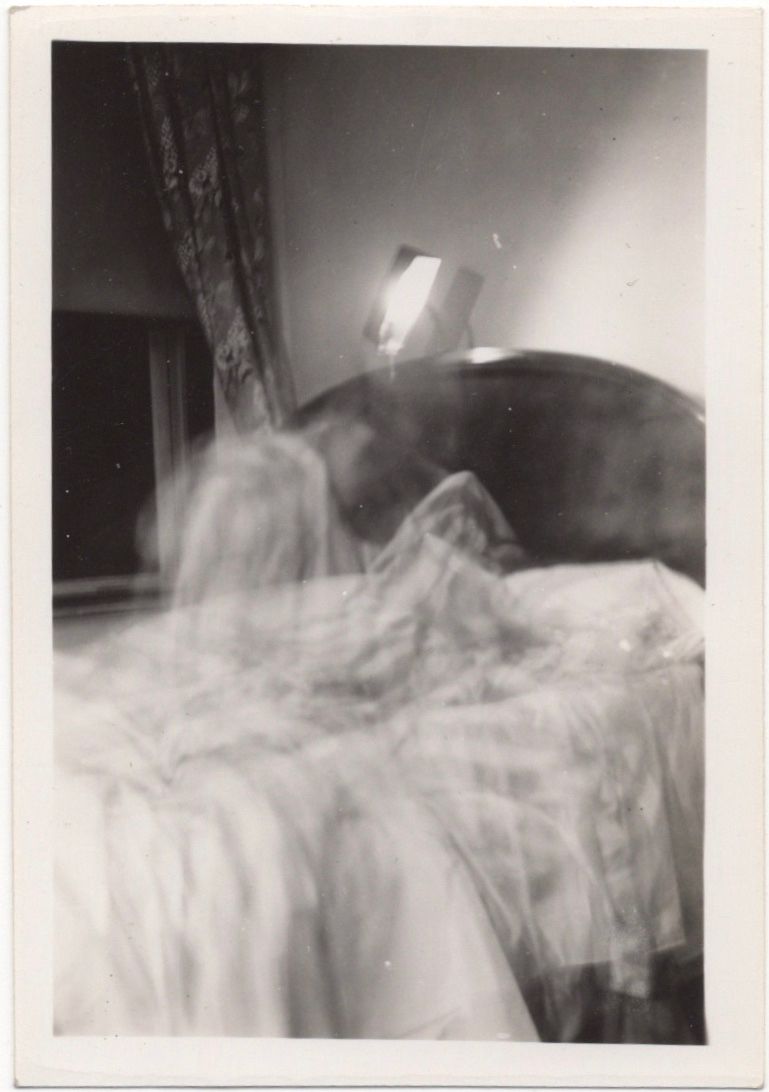

What made me start paying attention, more than forty years ago now, was a snapshot that I could only see as a small miracle. It looked something like a strange and novel art photo, one I already would have loved if a photographer had taken it. But I knew it hadn’t been deliberately created by a human being at all. Rather, it was the work of impersonal forces. There are literally billions of snapshots out there; most of them were taken with little care using low-grade equipment, then haphazardly developed and preserved. By great good fortune, a marvelous photo clearly brought into being or permitted by that very sloppiness caught my eye just when I was prepared to appreciate it. I liked it, I bought it, I took it home and tacked it up. After thinking about it for a while, I went out and looked for more. To me, at that point and for many years to come, snapshot photography was a great engine for producing and delivering into my hands a sort of dream art made by nobody, which for that very reason I felt free to think of as my own.

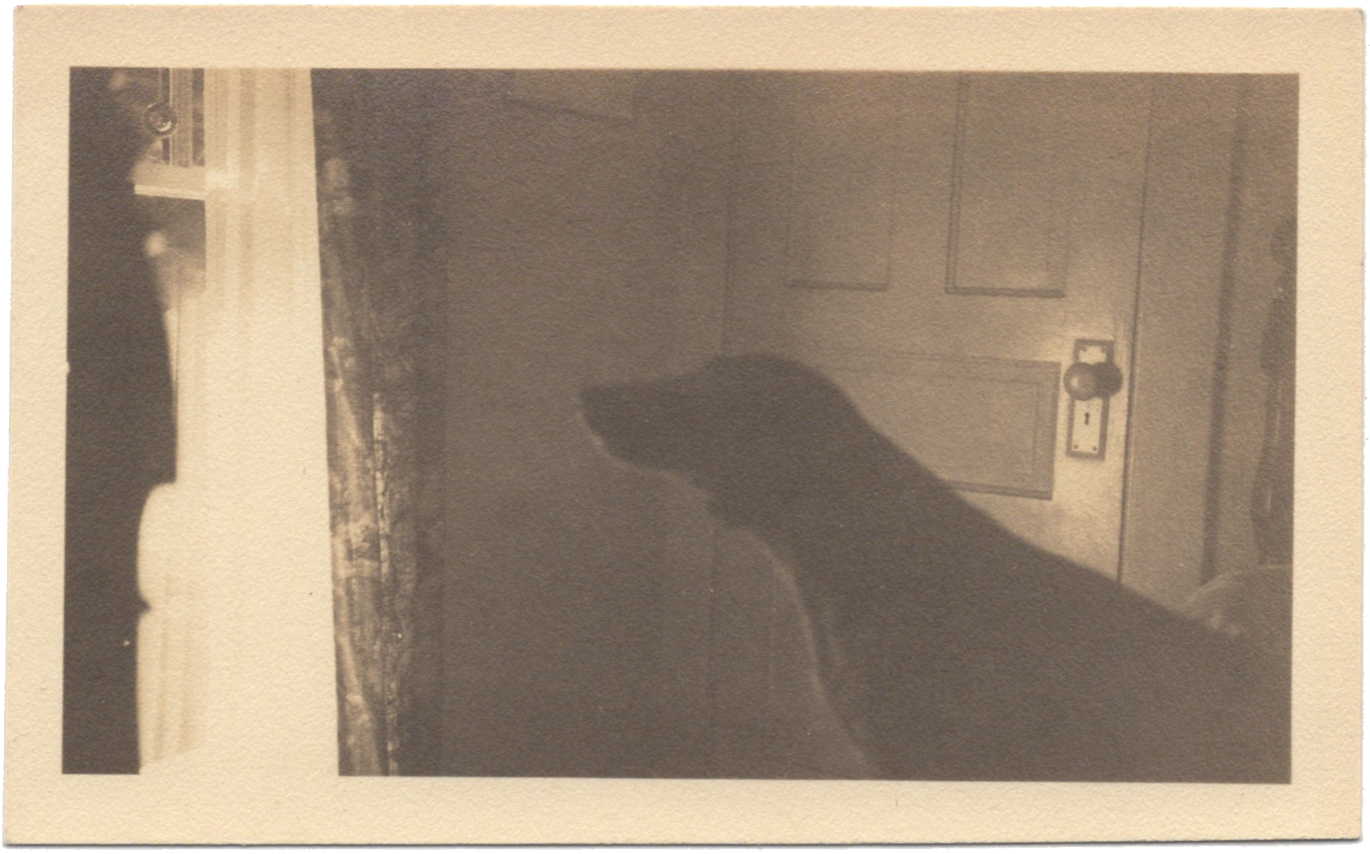

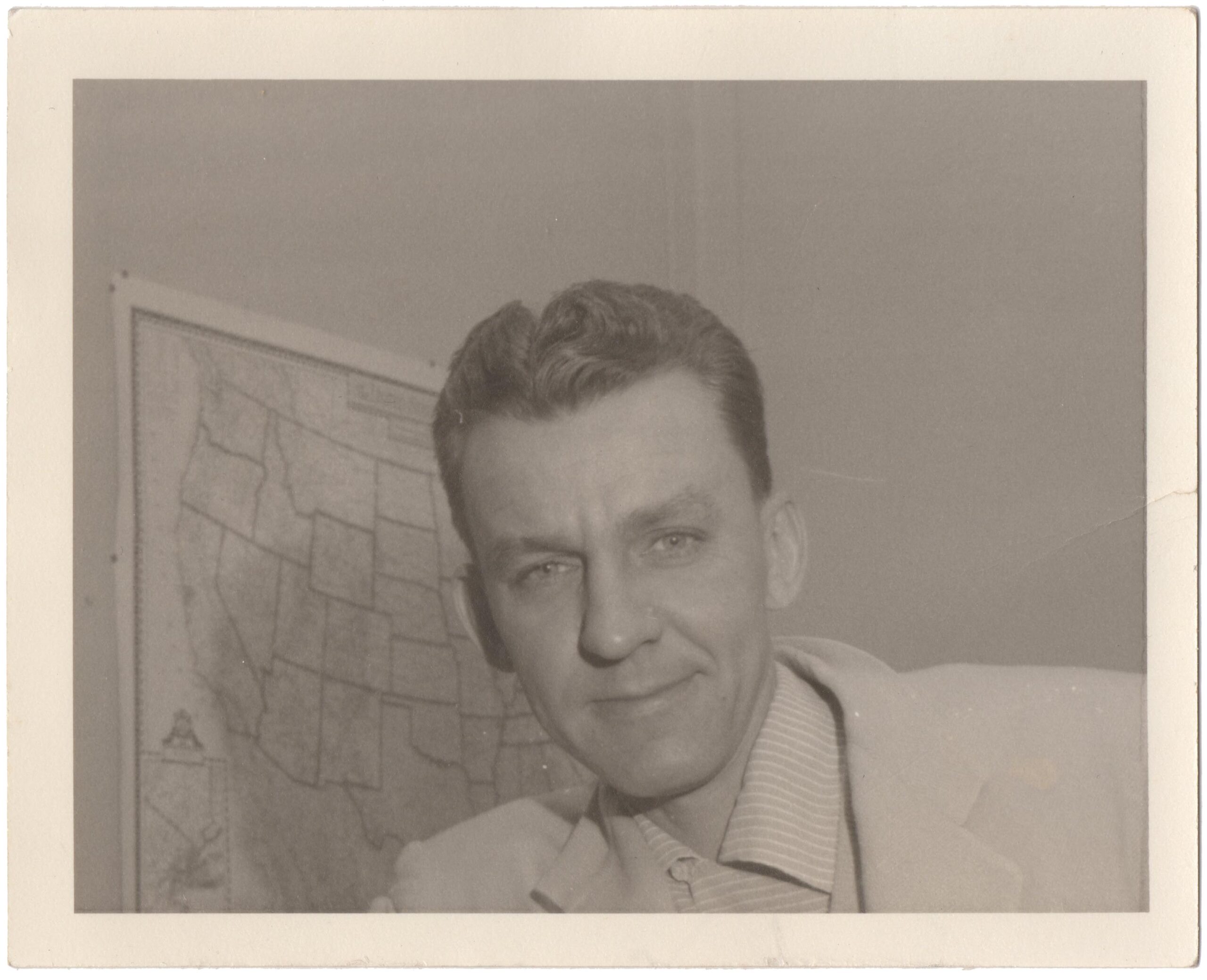

I was missing a lot here. Yes, the general vision was grand, if not grandiose. It involved fate, randomness, art and non-art, huge numbers and tiny probabilities, the impersonal universe and personal me. But somehow it didn’t involve people other than me at all. I hadn’t understood that snapshots are the special photos they are because of what they did for the people who took them and owned them. Everything about them goes back to their function as cheap, homemade personal mementos. That includes their physical characteristics (their modest size and poor technical qualities). It includes their objecty feeling (their physical preciousness above and beyond their value as images). It includes the frequent ingredient of casual experiment and fun (the cameras were, in part, toys). It includes the powerfully intimate documentary character of snapshots (people took their cameras everywhere). And it includes the pervasive element of chance, which was what first hit me so long ago. Every one of these aspects of snapshot photography (and I’ve skipped over quite a few) separates it from straight photography.

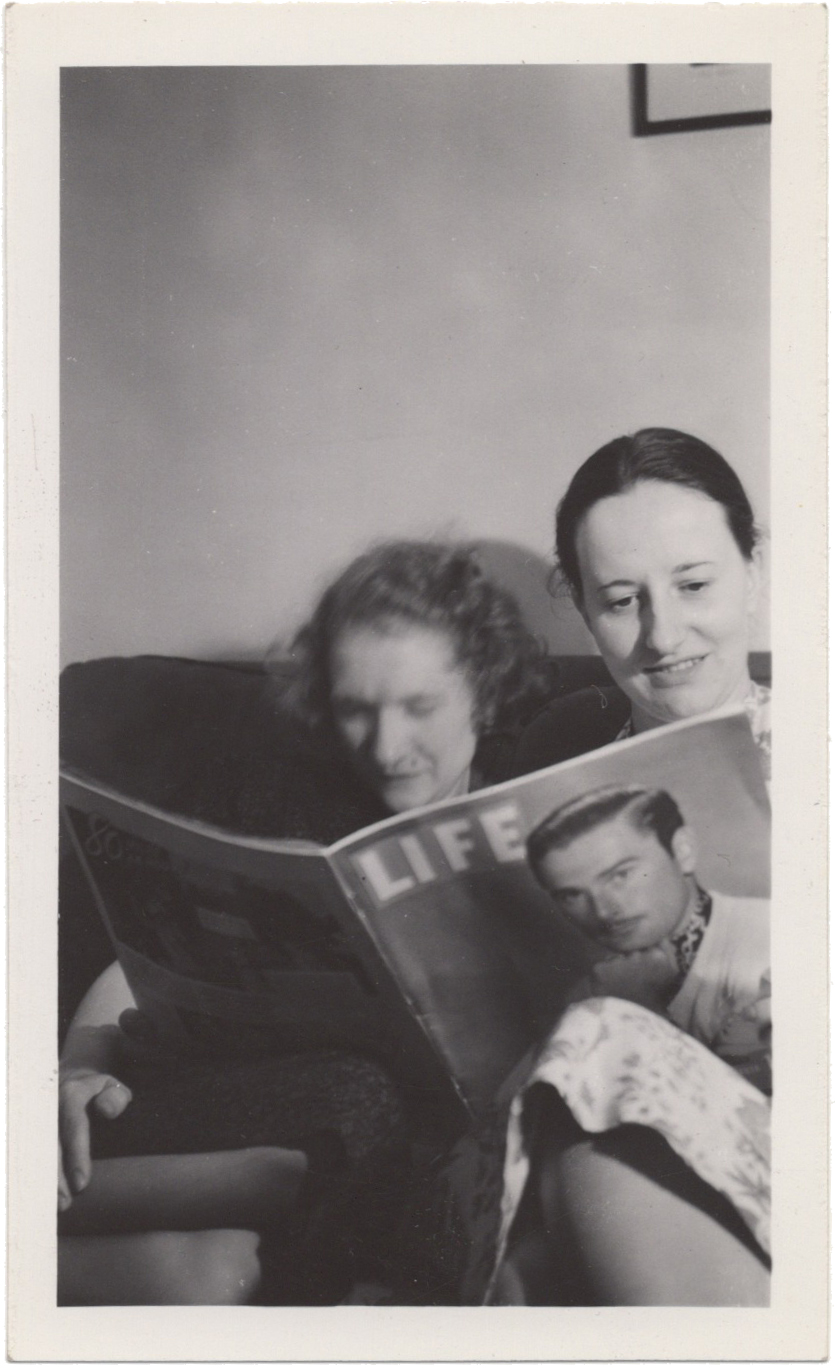

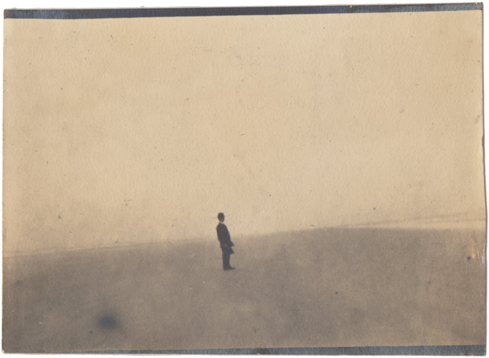

When snapshots first surfaced as an art-world phenomenon in the U.S., they were “found photos”—aesthetic repurposings in the Duchampian tradition, much like my own collection to that point. The photography collector Thomas Walther’s influential show, mounted by New York’s Metropolitan Museum in 2000, consisted entirely of one-in-a-million “found” snapshots that happened to fit with Walther’s own highly individual and refined taste in photography. He honestly didn’t care about the people in them and their lives, and it clearly hadn’t crossed his mind that snapshot photography was a form of its own. He had no interest in what made snapshots unlike art photography. On the contrary, all he cared about was how they were like art photography. This was a lot like my own original attitude, though Walther’s found style was not a personal discovery: it was an imitation of his eye as a collector of straight photography. And I suspect he bought at too high a level to have a realistic feeling for the statistical flukiness of his choices. The show was, in essence, a joke: “These freak shots look like the art photos I collect.” Even if Walther was in some sense harnessing one (and only one) true aspect of snapshot photography—the fact that you can find almost anything in it if you look hard enough—the show was absolutely not an exploration of the real corpus.

After 2000 the art world gradually changed its mind about snapshots. “Found photos” are out; “vernacular photography” is in. This term is now consistently used by art professionals in this country in treating snapshots as documents of social or photo history—as examples of what people have done with snapshot cameras beginning with the first Kodak. Aesthetic considerations no longer play a role. In fact a snapshot that’s “too good” by any modern photographic standard would be suspect in the contemporary context: no one wants to have to talk about the random factors that created that goodness and the aesthetic sensibility that called it good. Although snapshots in small quantities are now everywhere in American museums, they’ve apparently settled in for the long haul as quasi-academic snapshotological specimens. But the stuff is rarely treated well. No one thinks much of it, because it just doesn’t look like anything.

The eye of the curator or collector is irrelevant now: the assumption is that if you’re focused on what snapshot photographers were actually doing, anything about you is a distraction at best. But is this true? Consider news photos. News photos are about the news—about, ultimately, facts. The news itself doesn’t have aesthetic value. Yet the great news photos do: when they frame and dramatize the news as they have to do, when they lead the viewer to appreciate it, they are often as “personal” as work we are more accustomed to thinking of as art. Is that somehow a conflict? Are aesthetically-minded news photographers being unfair to the reality they’re recording?

Very possibly I was moving with the times when I began to care about how and why snapshots were made. But you can’t care about all of the virtually limitless snapshots equally, and not many of them show very much about the genre anyway. I care most when an actual person, me, likes both what they show and how they show it. I’d say now that my ideal snapshot is both a demonstration of something I consider important about snapshot photography and also a photo that I want to look at. The second part is personal, but also, I hope, fair to the genre; and I regard it as essential to really making the first part work. You don’t want to understand the significance of a picture unless it makes sense to you photographically.

Our job as collectors is first to notice something in the great snapshot corpus—some interesting truth of the genre—and then, perhaps, to make an effort to bring it out, to illuminate it in some fashion. Anyone who is fascinated by snapshots is aware that these are singular photographs, with their own ways of doing things. We’ve barely begun to tease out what those are. The U.S. scene, certainly the above-ground part of it, doesn’t see the potential here.